Silk Roads Beyond Borders

Tang Dynasty

Collection of Hong Kong Poly Art Centre

Length 61cm; Width 24.1cm; Height 79.4cm

Tang Sancai-glazed Bactrian Camel

This Tang Sancai-glazed Bactrian Camel is a masterpiece of tri-colored glazed pottery from the Tang Dynasty. Camels are classified as either single-humped or double-humped. Bactrian camels, with two humps, are native to Central Asia and northern China. As early as the Eastern Han Dynasty, camels appeared on brick reliefs in Sichuan, marking their early presence in Chinese art.

The Silk Road reached its peak during the Tang Dynasty. Camels, essential for crossing vast deserts, became powerful symbols of trade and a favorite subject for Tang artisans. Tang Sancai—literally “Tang three colors”—is one of the dynasty’s most iconic ceramic techniques. Surviving figurines often depict humans, animals, and foreign figures, including camels and horses.

As traded goods, Tang Sancai pieces traveled far beyond China. Fragments have been unearthed in West Asia and along the Mediterranean coast, reflecting the Silk Road’s global reach and the Tang Dynasty’s lasting influence.

Han Dynasty

Collection of Gansu Provincial Museum

Bronze Procession of Chariots and Cavalry

The Bronze Procession of Chariots and Cavalry is the preeminent treasure of the Gansu Provincial Museum. Unearthed from the Leitai Han Tomb in Wuwei, Gansu, the assemblage comprises ninety-nine pieces, the largest and most imposing discovery of its kind to date. At the very core of this grand procession stands the celebrated bronze galloping horse, once known as the “Galloping Horse Treading on a Flying Swallow.” On this occasion, twenty-four pieces are presented, including knights at the front bearing spears and halberds, mounted retainers behind with spirited steeds rearing and neighing, and two types of carriages: the light carriage with parasol, attended by charioteers, probably reserved for the tomb occupant or his high-ranking subordinates, and the wagon, accompanied by attendants, likely intended for the officials’ families. This ensemble vividly re-enacts the dignity and authority of a Han dynasty dignitary’s procession, offering a meticulous reconstruction of the hierarchical chariot-and-horse system. It stands as a microcosm of the Han empire’s governance of the Western Regions, its safeguarding of Silk Road trade, and the dissemination of Central Chinese civilization. Exquisitely crafted, the set exemplifies the advanced bronze-casting techniques of the Han period.

Modern Era

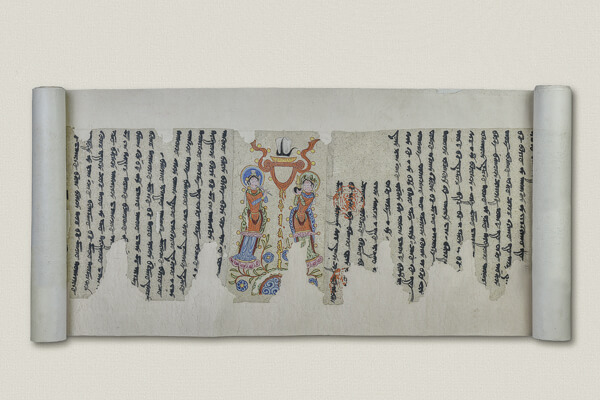

Collection of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum

Length 78cm; Width 28.5cm

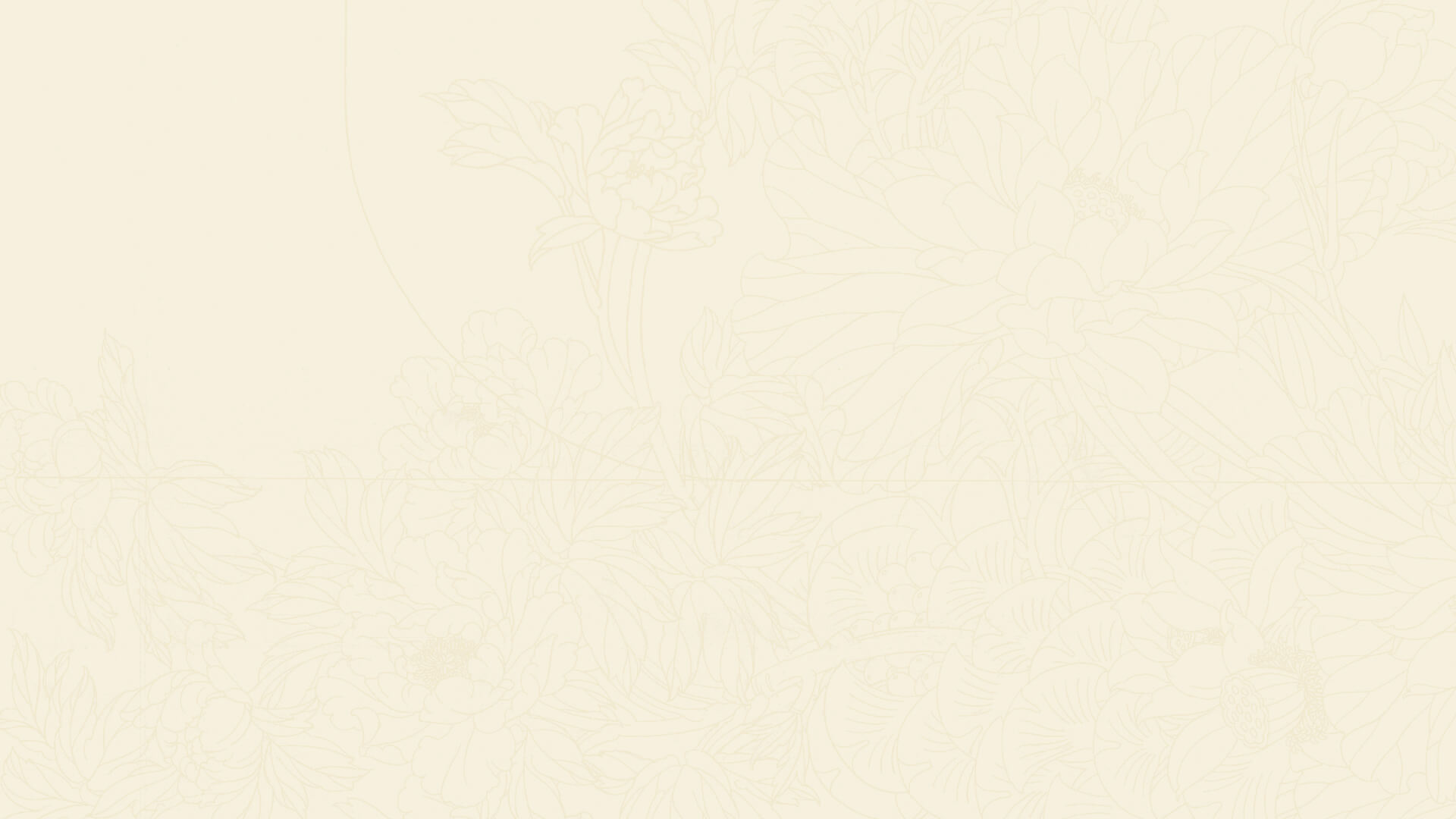

Travel Pass Issued by the Protectorate-General of Guazhou to Shi Randian, the Mobile General and a Commoner of Xizhou (Replica)

This guosuo was a travel permit used by a Sogdian merchant named Shi Randian, who lived in Xizhou—present-day Turpan in Xinjiang—when passing through frontier checkpoints in the Tang dynasty. The piece consists of three sheets of paper pasted together, preserving twenty-four lines of text. It contains two official documents, known as guosuo, issued by local authorities, recording Shi’s journeys to Guazhou and his trading activities en route to Shazhou and Yizhou. Guazhou corresponds to modern Jiuquan in Gansu, Shazhou to present-day Dunhuang in Gansu, and Yizhou to modern Hami in Xinjiang.

When passing checkpoints, guards would inspect the guosuo to ensure that the registered travelers and goods matched those actually in transit. This artefact vividly illustrates the commercial procedures and administrative formalities along the western segment of the Silk Road, while also demonstrating the effective implementation of imperial decrees by the Tang central government.

Northern Dynasties

Collection of Xi’an Museum

Diameter 2cm; Thickness 0.4cm

Byzantine Gold Coin

This gold coin, unearthed in China, was minted by the Eastern Roman Empire during the Northern Dynasties period. Its obverse bears the bust of Emperor Phocas, with flowing beard and dignified bearing, holding in his right hand a globus surmounted by a tall cross. The reverse depicts the figure of the goddess of Victory. Eastern Roman solidi have been discovered along many sites of the Silk Road, and in some regions local regimes even produced imitations, attesting to the prominence of the Byzantine Empire in Silk Road commerce and the rich cultural exchanges it fostered.

Exhibited alongside this piece are a silver coin of the Sasanian Persian Empire and a Jili coin of the Gaochang Kingdom (under the Qu clan) during the Tang dynasty, both significant witnesses to ancient Silk Road trade. The Sasanian coin features the portrait of the Persian king and motifs of a Zoroastrian fire altar, while the “Gaochang Jili” Coin may have been cast by the Tang court following the pacification of Gaochang as a commemorative amuletic coin, or alternatively produced by Gaochang itself for use as circulating currency.

Modern Era

Collection of Gansu Provincial Museum

Height 4.6cm; Mouth diameter 31cm; Bottom diameter 10.9cm

Byzantine Gilt Silver Plate with Dionysian Motifs (Replica)

This parcel-gilt silver plate, unearthed in Jingyuan County, Gansu, is a silver vessel in the style of the Eastern Roman Empire. The decoration consists of three concentric registers: in the middle ring appear twelve busts, likely representing the twelve Olympian deities of Greek mythology; within the central medallion reclines a nude male figure leaning against a lion, identifiable as Dionysus, the god of wine. According to the Book of Wei, the Eastern Roman Empire dispatched envoys to the Northern Wei court on three occasions. This piece may thus have been a tribute left by Byzantine emissaries at an ancient ferry crossing on the Yellow River, or alternatively a trade object brought into China by Western merchants during the period of the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern dynasties. It stands as a significant discovery along the Silk Road within China, and constitutes tangible evidence of cultural exchange between the ancient East and West.

Tang Dynasty

Collection of MGM

Left: Height 99.1cm; Width 47cm

Right: Height 102.2cm; Width 43.8cm

Tang Sancai Tomb-Guardian Beasts

These Tang Sancai tomb-guardian beasts are masterpieces of tri-colored glazed pottery from the height of the Tang Dynasty. Both are shown in a squatting posture, feet planted firmly on Sumeru-style pedestals. Standing nearly one meter tall, their massive, upright forms command a majestic and awe-inspiring presence.

Tomb-guardian beasts first appeared in Chu tombs during the Warring States Period and gained popularity through the Wei, Jin, Sui, and Tang dynasties. Designed to ward off ghosts and tomb robbers, they were deliberately rendered as fierce and intimidating to protect the souls of the deceased.

Tang Dynasty tomb guardian beasts combined diverse animal motifs. Lions—an imported form—featured prominently, while elements from Central Plains culture, such as the deer antlers seen in Warring States Chu tombs, were also retained. Some even bore human faces with features resembling people from the West, reflecting the vibrant cultural exchange between China and the West, fostered by the flourishing Silk Road.

8th–9th Centuries CE

Collection of Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum

Width 71.4cm; Height 16.2cm

Green Ground Weft-Faced Brocade with Holy Tree and Paired Deer Pattern

This textile is a Tang dynasty weft-faced brocade using the kesi (cut-silk tapestry) technique. Silk fabrics occupied a central role in the material and cultural exchanges of the Silk Road. As early as the Han dynasty, Chinese plain-weave patterned silk had already spread through the Hexi Corridor into Central Asia, exerting significant influence on the later development of the renowned Persian silks. Persian textiles are characterized by twill structures and distinctive pearl-roundel patterns enclosing animals or floral motifs. Inspired by these Persian designs, Dou Shilun, ennobled as the Marquis of Lingyang during the Tang dynasty, created patterns that placed auspicious Chinese animals within pearl roundels, thereby transforming the conventional linear, repetitive composition common in Central Plains textiles.

The present piece features, at its center, a sacred tree rising vertically, flanked on either side by a pair of long-horned deer, all encircled by elliptical pearl roundels—an arrangement known as the “Lingyang style.”

Around Ming or Qing Dynasty

Collection of MGM

Length 507cm; Width 451cm

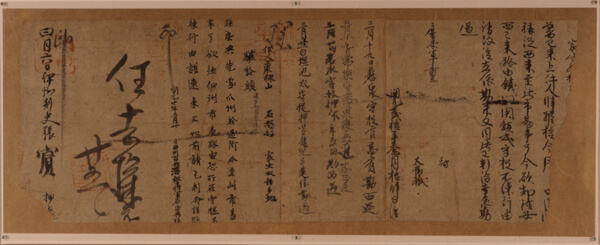

Dragon-Patterned Throne Carpet

The Dragon-Patterned Throne Carpet was woven using the wool pile-weaving technique, incorporating precious silk and gold threads. The texture is exceptionally dense, with colors that remain vivid and saturated. Its surface features motifs of paired dragons presenting a pearl, crashing waves against cliffs, and cloud patterns, all rendered in high relief, as if carved rather than woven. The refined craftsmanship and the remarkable state of preservation after several centuries make this an exceedingly rare masterpiece among silk textiles of the Ming or Qing dynasties.

The earliest known carpet in China, generally identified by scholars, dates to some 2,300 years ago from the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang. Such evidence demonstrates how the art of carpet weaving reflects the diffusion of cultures along the Silk Road. Persian carpets, celebrated along this route, in turn influenced Chinese weaving traditions, with Ming and Qing dynasty carpets incorporating both stylistic elements and technical features from these exchanges.

1730–1735

Private Collection, Hong Kong

Height 11.1cm

Meissen Hexagonal Tea Canister and Cover

This hexagonal porcelain tea caddy with lid was crafted in the 1730s by Meissen, the renowned European porcelain factory. Decorated with delicate motifs of insects, flowers, figures, and birds, it features Meissen’s signature Böttger glaze.

In the early 18th century, at the height of the “China craze”, Augustus II, Elector of Saxony, sponsored the founding of Meissen, Europe’s first porcelain factory. The factory mastered the use of kaolin, a key material in porcelain-making, and succeeded in producing hard-ceramic porcelain native to Europe. Early Meissen works often imitated the forms of Chinese porcelain, merging European craftsmanship with Chinese aesthetics.

This tea caddy embodies not only the technical exchange between China and the West, but also the cultural influence of Chinese tea. As a vessel for storing tea, it reflects the growing popularity of Chinese tea culture among the European aristocracy in the 18th century.

Ming Dynasty Hongwu Period

Collection of MGM

Height 33.5cm

Underglaze-Red Pear-Shaped Vase with Interlocking Floral Scrolls

This vase is decorated with underglaze red designs, arranged in layered registers that are intricate yet orderly. It belongs to the same category as the Underglaze Red Yuhuchun Vase with Entwined Peony Scrolls in the Palace Museum, both products of the Hongwu reign of the Ming dynasty. The prominence given to red reflects the Ming adherence to the cosmological doctrine of the “Five Virtues,” wherein the dynasty claimed legitimacy through the virtue of Fire, and thus esteemed the color red. The ornamentation is divided into seven bands: plantain leaves, key-fret pattern, billowing waves, ruyi-shaped cloud motifs, scrolling floral designs, upright lotus petals, and scrolling foliage. The scrollwork at the foot echoes that at the rim, forming a continuous, unbroken cycle. The principal decoration on the body is a scrolling floral motif featuring passion flowers, their blossoms rendered full and luxuriant, with branches arranged in graceful alternation. Underglaze red porcelains employ copper oxide as the coloring agent, which requires exceptionally precise control of kiln temperatures and carries a low success rate. This piece, however, not only survived firing successfully but also achieved a pure and vibrant coloration, balanced proportions, and elegant form, standing as a superb example of Hongwu porcelain.

Qing Dynasty Yongzheng Period

Collection of MGM

Height 60cm

Sacrificial-Blue-Glazed Ormolu-Mounted Vase

This vase with Western-style copper decorations was fired during the Yongzheng reign. The glaze, known as “sapphire blue”, gives the piece its rich, luminous color. It is adorned with copper Western-style motifs, including acanthus leaves and infant figures.

The technique of coating porcelain with copper and other metals dates back to the Song Dynasty and earlier. Originally used to conceal surface imperfections, it also enhanced the visual appeal of the piece.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Chinese porcelain was exported in large quantities along the Silk Road to Central Asia, West Asia, and Europe. Over time, the decorative role of copper coatings became increasingly prominent. Many European aristocrats even commissioned Chinese porcelain and employed specialized coppersmiths to add intricate Western-style copper embellishments, further elevating its value.

Yuan Dynasty

Collection of MGM

Diameter 16.1cm

Cloisonné Enamel Pine and Crane Tripod Dish

This three-legged incense tray, featuring a cloisonné enamel design of pine trees and cranes in spring, is a Yuan Dynasty artifact. It was crafted using the cloisonné enamel technique, commonly referred to as “Jingtai blue”.

Enamel craftsmanship is widely believed to have originated in ancient Greece, gradually evolving as it spread through Central Asia and Arabia before reaching China during the Yuan Dynasty. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, cloisonné enamel became a highly representative art form within the Imperial court, playing a prominent role in the decoration of various Imperial palace artifacts.

This piece, with its depiction of traditional Chinese motifs such as pine and cranes, not only conveys the symbolic beauty of spring, but also reflects the deep cultural and artistic exchange fostered along the Silk Road during the Yuan Dynasty.

Yongzheng Period, Qing Dynasty

Collection of The Palace Museum

Height 14.7cm; Mouth diameter 2.3cm

Octagonal Blue Glass Bottle, Yongzheng Period

This blue glass bottle, fashioned during the Yongzheng reign by the Imperial Glassworks of the Qing palace workshops, represents one of the finest examples of Qing dynasty glassware. An incised reign mark in two lines of regular script on the base reads “Made in the Yongzheng Reign.” In China, glass—historically known as liuli—was already being produced as early as the Western Zhou period, primarily in the form of lead-barium glass. Soda-lime glass, which is more transparent and originated in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, was introduced into China via the Silk Road during the Han and Tang dynasties. The craft of glassmaking reached its height in the Qing dynasty, when the range of colours and variety of forms achieved an unprecedented richness in the history of Chinese glass. This piece not only embodies the technical virtuosity of Qing glass production but also reflects the restrained and refined aesthetic sensibility characteristic of the Yongzheng period.

Sui–Tang Dynasties

Collection of Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum

Height 16.0cm; Mouth diameter 8.8cm; Base diameter 7.0cm

Gold Cup with a Tiger-Shaped Handle Adorned with Inlaid Red Carnelians

This gold cup with a tiger-shaped handle inlaid with red carnelian, dating to the Sui–Tang period, stands as one of the representative masterpieces of Tang gold and silverware. The vessel bears a handle in the form of a tiger, rendered in a Byzantine style with clearly discernible striations, while the body is set with oval red agates in mold-pressed lozenge-shaped panels, producing an impression of sumptuous splendor. The art of gold and silver filigree was a key domain of material and cultural exchange along the Silk Road. Originating in the Mediterranean world around 2000 BCE, these techniques gradually spread across Eurasia and entered China by the late Shang dynasty. Gold and silver vessels of the Sui and Tang dynasties made extensive use of such refined workmanship, while also incorporating stylistic elements from the western regions. Although this cup has suffered some deformation due to compression in antiquity, it nonetheless remains a vivid testament to the technical sophistication and aesthetic ideals of gold and silver craftsmanship during the Sui and Tang periods.

Tang Dynasty

Collection of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum

Diameter 3.8cm

Sesame Seed Biscuit

This sesame pastry, unearthed from the Astana Cemetery in Turpan, Xinjiang, is a Tang dynasty delicacy made from wheat flour, hand-shaped and baked, with sesame seeds adhering to its surface in meticulous detail. Exhibited alongside are two further pastries from Tang-period Turpan and a group of walnuts discovered in Qinghai. Together, they illustrate how sesame, walnuts, wheat, and numerous other foreign crops were introduced into China via the Silk Road from Central Asia, West Asia, South Asia, and Europe, thereby enriching the repertoire of Chinese culinary culture. Moreover, many foods familiar to us today—including watermelon, grapes, pomegranates, cucumbers, and garlic—likewise entered China through the channels of the Silk Road.

Tang Dynasty

Collection of Luoyang Museum

Length 12.5cm; Width 14cm; Height 29.4cm

Sancai Phoenix-Headed Ewer

This sancai phoenix-headed ewer, a Tang dynasty ceramic vessel, was fashioned using the celebrated Tang sancai (three-colour glazed pottery) technique. The handle is formed as a phoenix head extending from the neck, while the body is decorated on both sides with symmetrical motifs of phoenixes perched upon trees. The prototype of the phoenix-headed ewer is thought to derive from the “hu bottle” of Western and Central Asia, vessels often crafted in precious metals, characterised by a single handle, high ring foot, elongated upper body with rounded lower belly, and a spout shaped in the form of a bird’s beak, with surfaces adorned by figural or animal motifs. Introduced into China, the form underwent a process of localisation in which foreign cultural elements were adapted into native artistic traditions, ultimately becoming a vivid testament to Sino-foreign cultural exchange.

Tang Dynasty

Collection of Luoyang Museum

Width 15cm; Height 19.8cm; Mouth diameter 3.9-5cm

Flat Flask with a Central Asian Lion Tamer

This sancai flat flask with a beast-taming motif is a Tang dynasty ceramic vessel produced using the celebrated Tang sancai (three-color glazed pottery) technique. Flat flasks were a common form of wine vessel in the Tang period. On this piece, the shoulders are fitted with two perforated lugs, known as xi, through which cords could be threaded to allow the flask to be carried outdoors. The glaze combines yellow, green, and white, flowing and blending together at high temperatures to create a brilliantly variegated visual effect. The relief decoration depicts a scene of a foreigner taming a lion: on the left, the foreigner wears attire characteristic of the Western Regions, while on the right, the lion glares fiercely with eyes wide open, poised to pounce upon him. The depiction is vivid and dynamic, and exemplifies exotic cultural elements transmitted into China via the Silk Road.

Tang Dynasty

Collection of Shaanxi History Museum

Height 9cm

White Porcelain Pouch-Shaped Pot

This pot is a Tang dynasty porcelain vessel modelled after the water containers used by northern nomads. Beginning in the Tang period, ceramic craftsmen in the Central China adopted the form of leather pouch as a subject for porcelain production, a practice that continued in vogue through the Liao and Jin dynasties before gradually declining. On this piece, raised seams imitating stitched leather run along both sides of the body, while floral motifs decorate the upper section. The vessel is coated throughout with a lustrous white glaze, giving it a sense of fullness and solidity. It stands not only as a representative work of Tang white porcelain craftsmanship but also as a vivid reflection of the mutual influences between the lifestyles and artistic traditions of the Central Plains and the frontier regions, serving as a compelling testimony to cultural integration among different ethnic groups.

Eastern Jin and the Sixteen Kingdoms

Collection of Xi’an Museum

Length 19cm; Width 13cm; Height 26cm

Painted Earthenware Figurine of a Musician

This red pottery figurine, painted with polychrome decoration, depicts an musician from the Eastern Jin period kneeling as she plays the zheng, a classical Chinese zither. The musician wears a red cross-collared, narrow-sleeved blouse paired with a high-waisted long skirt. Her hair is arranged in layered strands parted to the sides of the forehead, while red cosmetic dots embellish her brow, eyelids, and temples—ornamentation characteristic of fashionable court makeup of the time. The zheng itself was not only integral to Han Chinese musical traditions but was also widely employed in the music of the Western Regions, including Liangzhou and Kucha. By the Sui and Tang dynasties, it had become a central instrument in the celebrated ensembles known as the “Seven Divisions of Music” and the “Ten Divisions of Music.”

Exhibited together with a pastel-painted figurine of a flutist, this piece exemplifies the flourishing exchanges in music and dance culture between the Central Plains and the Western Regions following the opening of the Silk Road during the Han dynasty.

1945-1948

Ink and Color on Paper

Length 102cm; Width 71cm

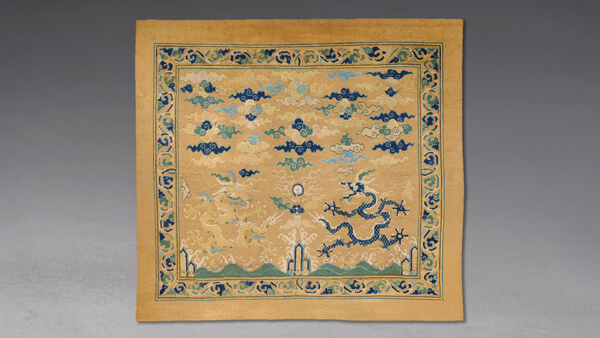

Chang Shana, Guanyin Bodhisattva

Guanyin Bodhisattva is a manuscript by the renowned inheritor of Dunhuang art, Chang Shana, copied from Dunhuang, representing the Tang period image of the Bodhisattva Guanyin. After the fifteenth century, with the decline of the overland Silk Road and the erosion of the natural environment, the Dunhuang caves gradually fell into neglect and even collapse. The sculptures, murals, and manuscripts preserved within—of immeasurable value—suffered severe damage and were once on the verge of disappearance. In the 1930s, Chang Shana’s father, Chang Shuhong, widely known as the “Guardian of Dunhuang,” was studying classical oil painting in Paris. By chance, he encountered an illustrated catalogue of the Dunhuang caves, which left him profoundly shaken. He resolved to return to China and devote his life to safeguarding Dunhuang. In 1943, Chang Shuhong established the Preparatory Committee for the Dunhuang Art Research Institute, thereby formally beginning the arduous journey of protecting the caves. For decades, together with his students and his daughter Chang Shana, he labored in the harsh environment of Dunhuang, racing against time by copying murals, reinforcing the cave structures, and cataloguing and documenting the relics. Thanks to their tireless dedication—and that of the many pioneers who joined them—these unparalleled cultural treasures have survived to the present day.

Exhibited together with this piece is another manuscript by Ms. Chang Shana, along with works and photographs by Mr. Chang Shuhong, all exceptionally rare exhibits. Also on display are manuscripts by distinguished guardians and inheritors of Dunhuang art, Professor Liu Yuanfeng and Professor Li Yingjun. Professor Liu, a former president of the Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology, reinterpreted elements of Dunhuang costume culture for contemporary fashion design, while Professor Li has sought to employ modern materials to recreate the attire of Heavenly Kings and Vajra guardians.

2nd–3rd Centuries CE

Collection of Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum

Width 36cm; Height 109cm;

Standing Buddha

The Standing Buddha is a Gandhāran-style statue dating from the 2nd to 3rd centuries CE. The Gandhāra region, located in present-day northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, occupied a unique geographical position and came under the influence of Greek, Persian, and Indian cultures. The Buddhist images created there embody the spirit of multicultural synthesis. In this example, the Buddha’s weight rests on a single leg, a stance clearly indebted to Greek artistic traditions. His right hand performs the abhaya mudrā, the gesture of fearlessness symbolizing salvation, a motif derived from divine and royal imagery in Western Asia. Behind him, the circular nimbus represents one of the symbols of Iranian culture, evoking the concept of the “divine within humanity” in the world of infinite light. Gandhāran Buddhist sculptures later spread eastward with the transmission of Buddhism into China, leaving a lasting impact on the development of Chinese

Eastern Han Dynasty

Collection of Mianyang Museum

Length 32cm; Width 24.5cm; Base height 52.1cm; Overall height 150cm

Bronze Money Tree, Eastern Han Dynasty

The Bronze Money Tree was unearthed in Mianyang, Sichuan. This tree-shaped bronze, with branches hung with coins, is known as a “money tree” (yaoqianshu). Such artefacts are generally regarded as the outcome of a fusion between indigenous Daoist thought and religious concepts introduced from the West during the Eastern Han period. They enjoyed wide popularity at the time in regions such as Sichuan, Chongqing, Yunnan, Guizhou, and southern Shaanxi. Beyond the numerous coins symbolizing abundant and unceasing wealth, the branches of money trees were often adorned with auspicious animals. Some examples even bear miniature Buddhist figures, reflecting the eastward spread of Buddhist ideas. The Queen Mother of the West (Xiwangmu) also frequently appears, as she was believed to possess the elixir of immortality and the power to grant transcendence and eternal life.

Northern Song Dynasty

Collection of Turfan Museum

Length 268cm; Width 26cm

Sogdian Text Document Scroll of the 9th–13th Centuries

The Sogdian Text Document Scroll of the 9th–13th Centuries is a Tang dynasty manuscript written in the Sogdian script, consisting of correspondence among Manichaean adherents of the time. Its contents include mercantile contracts, religious texts, and diplomatic letters, along with records of camel numbers and spice prices, providing valuable data on contemporary trade practices. The piece is composed of nine sheets of paper joined together, bearing a total of 135 lines of text. Between the lines appear finely painted illustrations of musicians, together with headings rendered in gold, serving as ornamentation.

The Sogdians, who inhabited the region between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers in Central Asia, were a people especially skilled in long-distance trade and are considered the most representative merchant community on the Silk Road between the 4th and 8th centuries CE. Their principal faiths were Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, and while engaging in commerce along the Silk Road, Sogdian merchants also transmitted religious beliefs. This manuscript is therefore of great significance for the study of Manichaean activity in Eastern regions, as well as for understanding the history of the Silk Road.

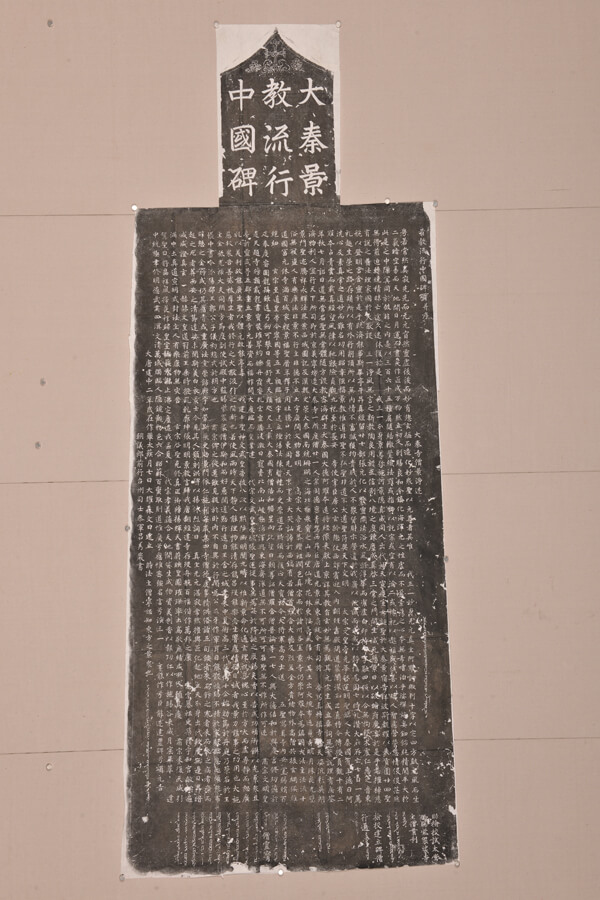

Modern Era

Collection of Xi’an Beilin Museum

Width 91.5 cm; Height 244.5cm

Rubbing of Daqin Nestorian Stele (Replica)

The Rubbing of Daqin Nestorian Stele (Replica) reproduces the original Tang dynasty monument that bears witness to the dialogue between ancient Chinese and Western civilizations. “Daqin” refers to the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, while “Jingjiao” denotes the Nestorian branch of early Christianity introduced into China during the Tang period.

The inscription, composed by a Persian missionary, provides a detailed account of Jingjiao doctrine and liturgical practices—including baptism, mass, and prayer—as well as the history of its mission in China from the ninth year of the Zhenguan reign (635 CE) through the second year of the Jianzhong reign (781 CE), nearly two centuries in total. The text further interprets Christian teachings through the lens of traditional Chinese philosophy, exemplifying the localization of foreign belief systems within Tang culture and standing as a significant testimony to the integration of outside traditions into the Chinese intellectual and religious landscape.

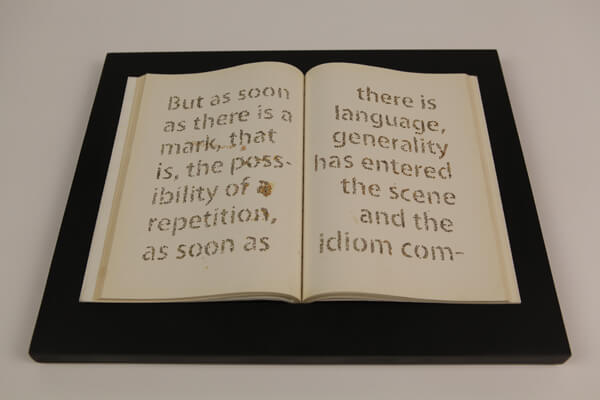

1994-1999

Mixed media installation; Video

Xu Bing, American Silkworm Series

The Silkworm Series in America is a work by the internationally acclaimed Chinese contemporary artist Xu Bing. On view here are two pieces from the series: Book from the Silkworm and Wrap. From 1994 to 1999, every summer I raised silkworms in the United States, creating works together with them. One group of works is Book from the Silkworm. In this process, silkworm moths deposited their eggs onto the blank pages of a pre-bound book. The patterns of eggs printed on the pages resemble a mysterious script. After the exhibition opened, the eggs began to hatch into larvae. The black dots disappeared, replaced by thousands of moving “black lines” (the larvae) crawling out of the pages, unsettling viewers who felt that something had gone wrong with the books. Another group, titled Wrap, involves hundreds of silkworms spinning silk around a book. As the days passed, the silk thickened; the texts or images legible at the exhibition’s opening gradually faded and then vanished. By the end of the show, the object had become transformed into something strange and enigmatic.

1931

Oil on canvas

Private Collection, Hong Kong

Sanyu, Bouquet of Marguerites

Sanyu was an early renowned French painter of Chinese descent and a representative Oriental artist in the School of Paris. Within Western modernist thought, he reinterpreted Chinese artistic traditions, creating a unique aesthetic that transcended cultural boundaries. Recognized by Western art circles as an outstanding Eastern painter, he was often referred to as the “Matisse of the East”. Floral subjects were among his main creative themes.

Bouquet of Marguerites features elegant lines and refined colors, fully expressing the traditional Chinese painting concept of “five colors in ink”. It also incorporates the Western concept of three-dimensional perspective into the flat narrative space of Eastern art. This work is one of Sanyu’s representative pieces from the 1930s.

1951

Oil on canvas

Private Collection, Hong Kong

Zao Wou-ki, Untitled (Golden City)

Zao Wou-Ki was a renowned French artist of Chinese descent, often mentioned alongside Wu Guanzhong and Chu Teh-Chun as one of the “Three Musketeers” of Chinese artists who studied in France. He gained international recognition for combining Western abstract painting techniques with the ethereal qualities of Chinese painting. His works are held in major institutions including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Guggenheim Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris.

In the 1950s, Zao Wou-Ki began a European journey that he considered a key stage in his life, one that brought continuous inspiration. Untitled (Golden City) is an important work based on his impressions of Venice, Italy. The painting still includes lines depicting churches and palaces, reflecting his early style. Later, Zao Wou-Ki fully embraced abstract art. Another work in this exhibition, 13.02.62, is a key example of his abstract style.